A lanky, dark-haired man strolls over to me in the car park. I am standing there making final adjustments to my pack. It bites into my shoulders loaded with winter walking gear and a couple of days of food.

"Have you seen any lyrebirds on your walk," he asks.

At this stage, I haven't been on my 'walk'. I am waiting for Caz, who is in the Visitor Information Centre at the entrance of Girraween National Park, in southern Queensland. We are about to start an overnight exploration around Mt Norman, the highest peak in the park at 1,267m.

Fortunately, for the lanky man beside me, we made a quick dash up The Pyramid the previous afternoon (a stunning granite outcrop which rises out of the forest and points to the beckoning blue sky). I tell him that I certainly heard lyrebirds in the deep gully below the walking track. Winter is the lyrebird's mating season and it is when they are most vocal. As we are 9 days into that season the amazing mimicry and vocalisations of a singing male had rung clearly through the forest all afternoon. I tell him this as if I am a kind of local lyrebird expert. I am about to learn, however, not to boast to strangers.

The friendly man is, in fact, a lyrebird specialist, a biologist and zoologist from the University of Western Sydney, travelling with a research student from Cornell University and studying the Superb Lyrebirds in Girraween to examine whether the population here is its own sub-species. He says the local Superb Lyrebirds are the most northern population in Australia and due to their isolation from other populations it is believed they also have their own language. But they have been searching unsuccessfully for two days and have just one day left. Time is running out to hear this most unique of unique songs.

I love learning this kind of new information about our amazing Australian wildlife, that there are subspecies and secret languages amongst our most famous birds. I also love the lesson that one should always be open to conversations with strangers, especially in National Park car parks. A chance encounter, a well-placed question, can change your perspective. Superb Lyrebirds are already one of our favourite Australian animals and we have had some amazing close encounters in the wild, often while exploring off-track. The clarity of their call and exactness of their imitations is continually astounding (see wildambience website for examples). That separate populations may have different languages is just another string in their incredible bow and as we set off walking I find myself listening to this wild place with a more open, keen ear.

As the lyrebird experts set off in the direction of The Pyramid, we leave the main visitors information centre taking the walking track towards The Castle, another granite peak with commanding views across the valley. The walk begins with some steady ups, but it is a good track, with extensive stone steps. The first creek we cross has good water but the second is not flowing, with only small, rare pools. We plan to stay out overnight, and camp high, so are carrying the water we need - 6 litres between us. I am still waiting for a light-weight version of this life-giving, bushwalking essential!

Passing the turn-off to The Castle (we have visited it previously), we enter a patch of forest dense with low banksia shrubs in profuse bloom. Big orange candlestick flowers are under attack from New Holland honeyeaters. These tiny black, white and yellow birds dart furiously through the trees, missing my head by inches. Girraween is actually an Indigenous word meaning ‘place of flowers’. Although the word is not of local indigenous origin, it is an apt name for this park, which produces spectacular spring wildflower displays and, in this case, a pretty spectacular winter display as well. We see more than half a dozen honeyeaters in this one small grove. They alight briefly on each flower before dashing to the next in a flurry of sugar-fuelled activity.

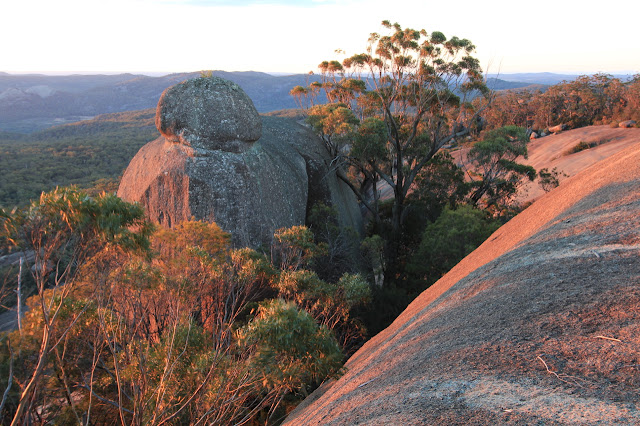

On the long, steady climb up Mt Norman the views are fantastic. To the north-east is Bald Rock and even the distinctive top of Mt Lindesay cutting the horizon about 90km away, as the crow flies. South of us looms West Bald Rock and swinging around to face west I see range upon range and among those mountains lies Sundown National Park. Not until we get higher can we see across the nearest ridges to some features closer at hand in Girraween - The Sphinx and Turtle Rock. As they draw into view, we point and discuss the intervening landscape with the discerning eye of explorers. It looks fun in there - slabs of rock, deep gullies, forest littered with boulder upon boulder. It looks like a terrific off-track alternative for our return journey.

An information sign at the 'top' of the climb onto Mt Norman leads us north-east on a short side track to view The Eye of the Needle, an collection of balancing rocks - a combination of weathering and fractured placement. Geology at its most interesting. After a quick lunch, we chose to leave our packs at the sign and begin exploring the mountain. It takes rock climbing equipment and experience to reach the true 'top' of Mount Norman but without that kind of gear on board we still find terrific lookouts. After the sign, the walking track winds along the western side of the mountain, zig-zagging through the forest and under rocks before turning sharply east, through an enchanting alley of granite to emerge on the other side of the mountain. We scout around for a campsite, heading further south-west, clambering along granite ledges, climbing boulders and sneaking through breaks in the rock. We work our way around to a narrow, lush gully and run head-on into one of those unique Superb Lyrebirds, foraging in the fernery and quite happy to wander right past us as we crouch quietly watching it pick its way delicately through the scrub. But, it is a female and therefore not as profuse a singer. It moves on quietly and intently and, eventually, so do we.

One of the best viewing spots on Mt Norman is the old trig cairn: a massive construction of rocks, neatly formed and holding an old wooden post. The cairn itself is not signposted from the track, and is a little tricky to find, following a faint footpad that seems to dead-end before another of those typical zig-zag manoeuvres into another granite alleyway. Tonight, the cairn is a perfect spot to view a rich purple and orange sunset with a long afterglow as the sun goes wandering west.

After a star-rich night, tucked away on the southern end of Mt Norman, the next day the fun begins - offtrack down all those sloping pavements of rock, heading for Turtle Rock and The Sphinx. We set off at 8:13am, leave the main track and head straight down the steep, open face that rolls westwards off Mt Norman. Luckily there is water to top up supplies, near the bottom of the slope, where all the seeps join into one decent trickle before disappearing and dispersing into thick ferns in the gully below. Once we enter this gully though, the walking slows considerably. The ferns obscure a mess of fallen limbs, fallen trees, rocks and old wombat holes. We balance and climb and gingerly reach each foot forward before committing to a step. Climbing onto the next ridge is slow and steady and following the path of least resistance. At the top, again the reward is great views. This time back to Mt Norman and ahead to The Sphinx and Turtle Rock. And again, we have good slabs of granite to follow all the way down into the next gully. There is a bit of zig-zagging to dodge thickets of scrub but we pass lovely rocks teetering miraculously on the slabs. We follow water furrows coloured black and gold and shimmering in the sunshine. For the climb out, The Sphinx is our guiding high point but, as we get closer, the perspective changes and it loses its distinctive shape. It disappears behind trees, hidden by the angle of the slope.

As we navigate our way upwards, there is nothing amazing to see but it is great fun and absorbing walking. Off-track adventure takes your mind off everything but the moment - we are completely focused on where to step, what to move out of the way, which direction to take. It's part of its appeal. One of my favourite quotes about off-track walking comes from the excellent Caro Ryan on her blog Lotsafreshair.

She says: "Without realising it, I’d built invisible walls each side of tracks or trails that I walked upon. Remember Wonder Woman and her invisible plane? Well these walls were kinda like that! The shock I had that first day breaking through that invisible wall happened when we stopped at a certain point on what was a perfectly good single-track and the leader (after checking map and compass) declared, “Here we go… into the great unknown!” I could see for the first time that there really were no walls to the ways in which I could experience wilderness and nature."

Finally, The Sphinx looms above us and we emerge onto the walking track and dust the leaves and sticks from our hair. It has been one of the shortest but most enjoyable off-track jaunts we have had for a long time. Ahead is an easy, 3km walk along a formed trail which will take us back to the car. Surprisingly, in the moist gullies we have heard no lyrebird calls. I am glad we were able to point the researchers to the song makers we heard beneath The Pyramid. I wonder how they went, pushing through some of this tough scrub, and then listening to that amazing song and trying to understand their unique language. I hope for them it is successful, that they have heard the special song of this wild place and that information will help us all respect and appreciate the need to conserve these wild lands where birds sing songs in strange tongues.

All images and words on this site are copyright of Craig Fardell and Christina Armstrong. It is illegal to sell, copy, or distribute images and text without permission. We thank you for your help in respecting the copyright of our work.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.